Continuing our series of interviews with Future Observatory researchers, we’d like to introduce Nick Dunn and Rupert Griffiths – the academic contingent on Sonorous Landscapes: Using Sound and Urban Design to Capture and Communicate Biodiversity in an Urban Forest, a Design Exchange Partnership led by Lancaster University.

Design Exchange Partnerships bring academic researchers together with non-academic organisations, such as businesses, NGOs or local councils, to address challenges relating to the green transition.

In conversation with Future Observatory coordinator Leilah Hirson-Comley, Nick and Rupert share how their Design Exchange Partnership is exploring new ways to record and experience urban biodiversity.

LHC

To begin with, could you introduce yourselves and your research project?

RG

I’m a Senior Research Associate at ImaginationLancaster – the design and architecture research lab at the Lancaster Institute for Contemporary Arts. I have a background in architecture and urbanism and I define myself as a human geographer, a design researcher, and an artist.

My current research asks how urban and human-altered landscapes can be made legible as more-than-human ecologies. I am interested in how this contributes to a recalibration of urban imaginaries – the shared visions and perceptions of urban life – and design research practices away from the anthropocentric towards eco-, bio- and cosmo-centric positions.

ND

I’m the Director of ImaginationLancaster and the chair of Urban Design at Lancaster University. Like Rupert, I have a background in architecture and an interest in using design research methods and creative practices for audience engagement.

With this project – particularly the practice-based work that Rupert’s been driving – the aim is to engage communities with issues affecting urban biodiversity, such as habitat loss, conservation and rewilding initiatives. By finding new ways to represent environmental data from urban environments, we are trying to show people – particularly those in urban communities – that we all have a stake in biodiversity.

LHC

How does your project support urban communities to engage with biodiversity, and why is this important?

RG

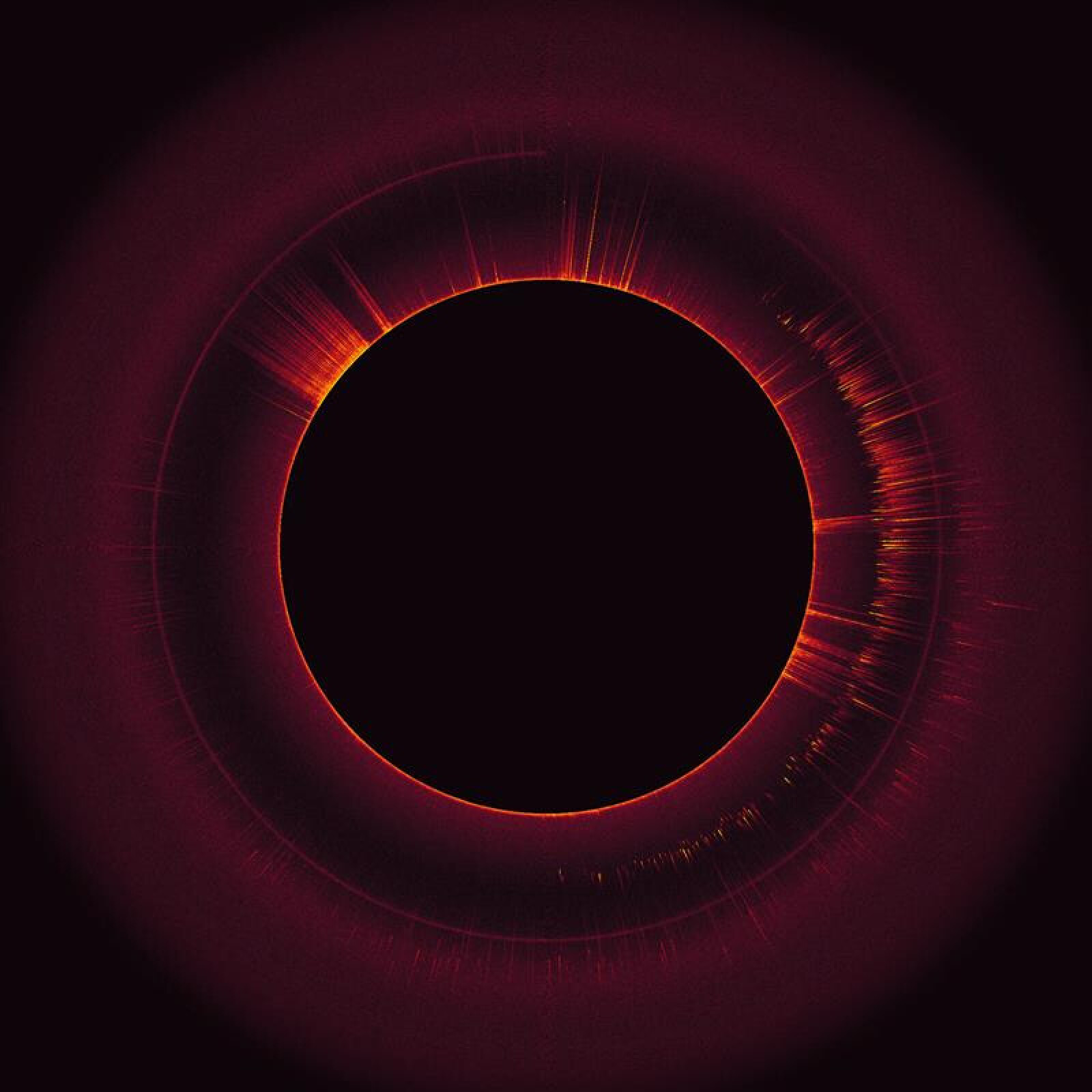

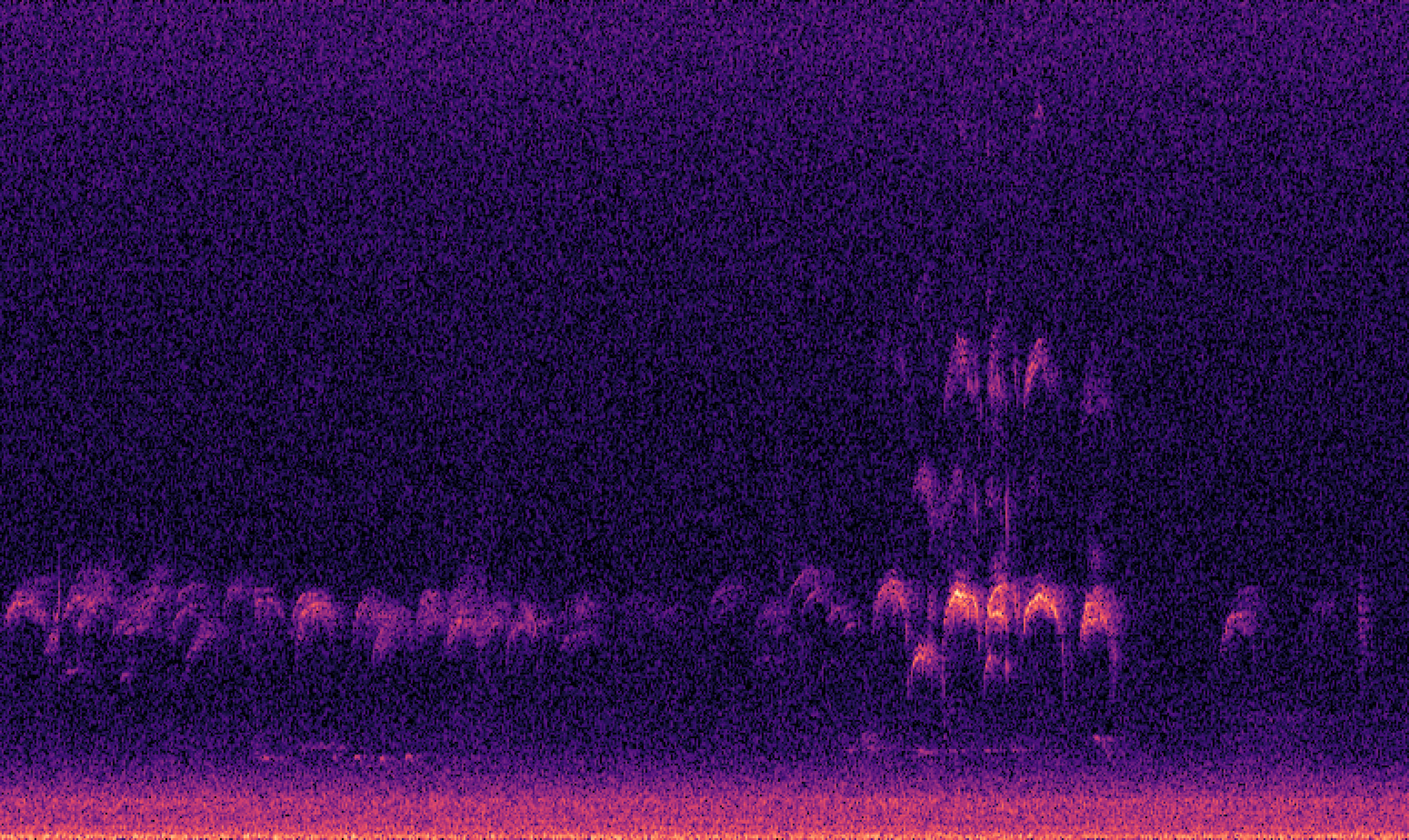

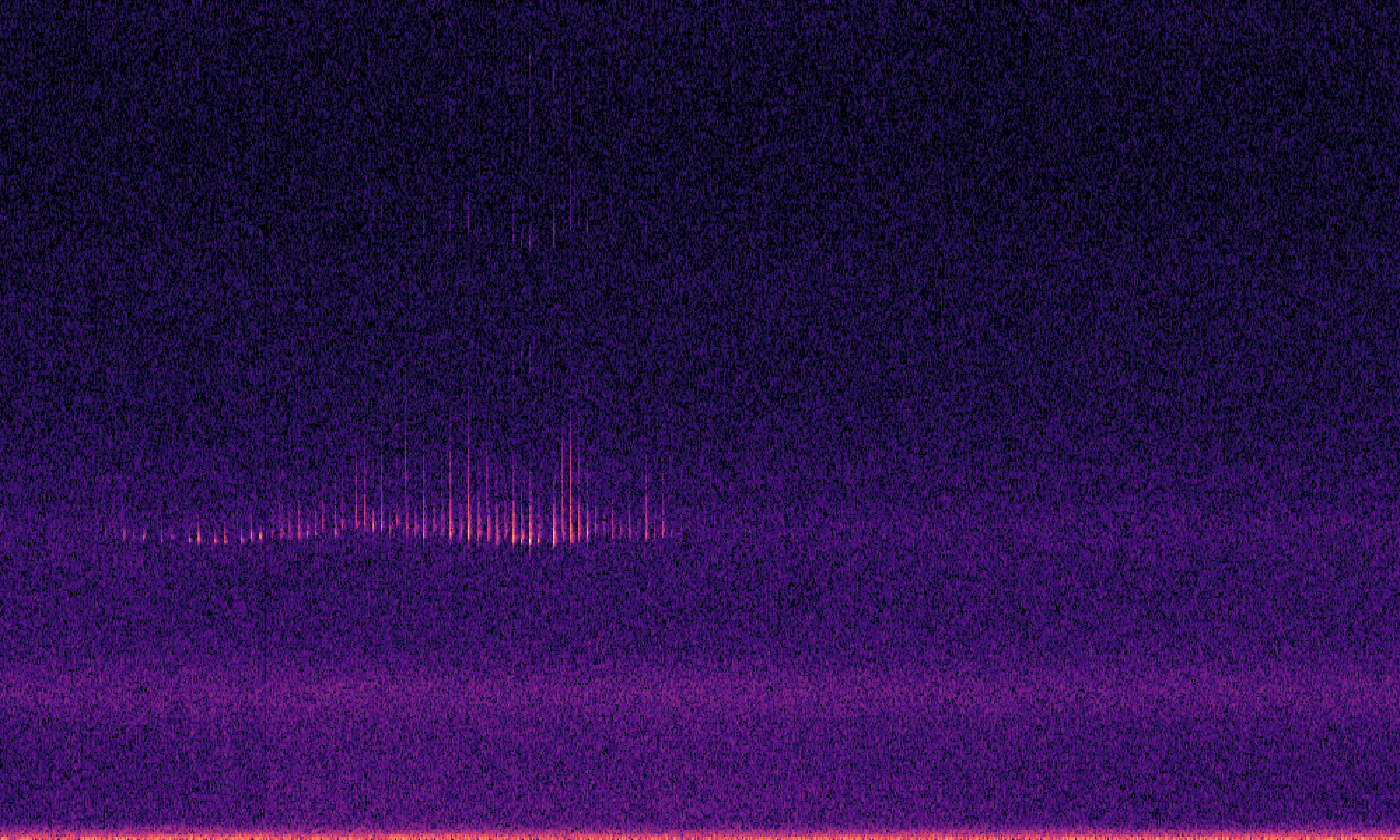

Rather than simply telling urban communities to protect biodiversity, our approach is to raise awareness of its presence and highlight its interconnectedness with the human-made world. The use of sound is helpful here because it evidences vocal organisms: human activity in the low frequencies, birdsong in the audible frequencies and insects and bats in the higher frequencies. Ultimately, we’re trying to take an ecological approach: presenting the urban landscape as a complex group of agents, actants and processes; the biological interacting with the non-biological, technological and meteorological.

ND

Most of us don’t think about urban places as being ecological. It wasn’t until we were in lockdown a few years ago and human activity stopped, or at least significantly reduced, that we even became aware of biodiversity in our urban environments. This project aims to reveal latent data – the non-human sounds in our urban landscapes and the more-than-human species creating them – to show that biodiversity is a part of our everyday (and night) experience.

As visually attuned creatures, we predominantly make sense of our surroundings by looking rather than listening; for most of us, hearing is a secondary sense. However, through understanding how our urban spaces sound we can foster a greater appreciation for urban nature and support efforts to promote environmental stewardship.

LHC

Your project explores new ways to represent environmental data and urban nature. How will this help to drive the green transition?

ND

The news frequently presents us with statistical data on biodiversity – the decline of animal populations or the increase in pollution, for example. However, the numbers are quite hard to relate to, and after the initial thought of ‘that is really bad news,’ we tend to just scroll on. This project attempts to make that data more relatable, connecting people to it in a way which supports advocacy and commitment to action.

RG

Imaginaries of urban nature and the relationship between nature and culture are big drivers for the adoption of policy. People are more inclined to support green transition policies if their urban imaginaries are positively aligned with green agendas. So, the construction of ideas about nature and culture is central to how people behave and vote.

ND

Representations of a place are also very persuasive; they enable people to engage with ideas about how a place might change, and you can galvanise people behind those ideas. Projects such as ours are trying to find new ways of talking about biodiversity in the places in which we live in support of bigger strategic aims, like the green transition. In this case, arts and humanities research – particularly design research – is vital for initiating these conversations and offering alternatives to “business as usual”.

LHC

What are the benefits of partnering with your local council (Slough Borough)?

RG

There’s a complex political situation in Slough that is indicative, I think, of the kind of situation that has been unfolding across local authorities in the UK over the past year or two. Resources are limited, and funding for non-essential environmental maintenance work, such as tree planting and watering initiatives, has been cut. Complex contexts like this present a challenge to green transition agenda projects, but this is not a challenge that can’t be overcome. We’ve got partners in the council who are well-equipped to navigate these issues, so it’s been a positive partnership to embark upon.

ND & RG

Programmes like the Design Exchange Partnership scheme foster a collaborative ethos that doesn’t exist in more conventional research projects. That’s important because it means that all the project participants can have a real exchange of knowledge and ideas; this is what our project is hoping to support going forwards. Difficult times lie ahead but the fact that the council is dedicated to this process is a very good sign.

LHC

Where do you hope this research leads to in the future?

RG

Our project has piqued the interest of quite a few community organisations in Slough, including Friends of Slough Canal, Stoke Road (Cherry Orchard) Allotment and the Green Slough Community Development Trust. They have overlapping membership with the council and are very well organised, so they are well-positioned to continue work that the council is no longer able to fund. I think collaborating with these groups is the way forward in this region.

However, I see this as a planetary rather than a local issue. Slough has a very diverse community, and many of the people I’m working with have families in countries that are directly affected by climate change. This global awareness creates an understanding of the planetary scale of the climate crisis, and I can see this project moving in an international direction in the future.

ND

Apart from our ambitions to undertake further research projects, we want to facilitate change in policy, practice and behaviour. That starts with engaging the public and getting people to really care about the environment. Many people do care, but climate change is so massive that it’s easy to get stuck asking “How can I make a difference to what is happening in the world?” Perhaps it sounds overly simple, but I think that just listening to what the world is doing is a good place to start.

*This interview has been edited for length and clarity.