In late May, we held a networking event at the Design Museum for the researchers and industry partners involved in our Design Accelerator, Design Exchange Partnership and Design Researchers in Residence research programmes. The day began with presentations and project updates from each of the 19 research teams in attendance. We also heard from Allan Sudlow, Director of Partnerships and Engagement at the Arts and Humanities Research Council, who gave a talk on the various strategies for engaging and influencing policy-makers. Rounding off the morning, we were joined by Professor Fabrizio Nevola, Head of Art History and Visual Culture at the University of Exeter, who presented a detailed case study on how a research project – in this case, an app for urban history tours – can evolve into a self-sustaining business venture.

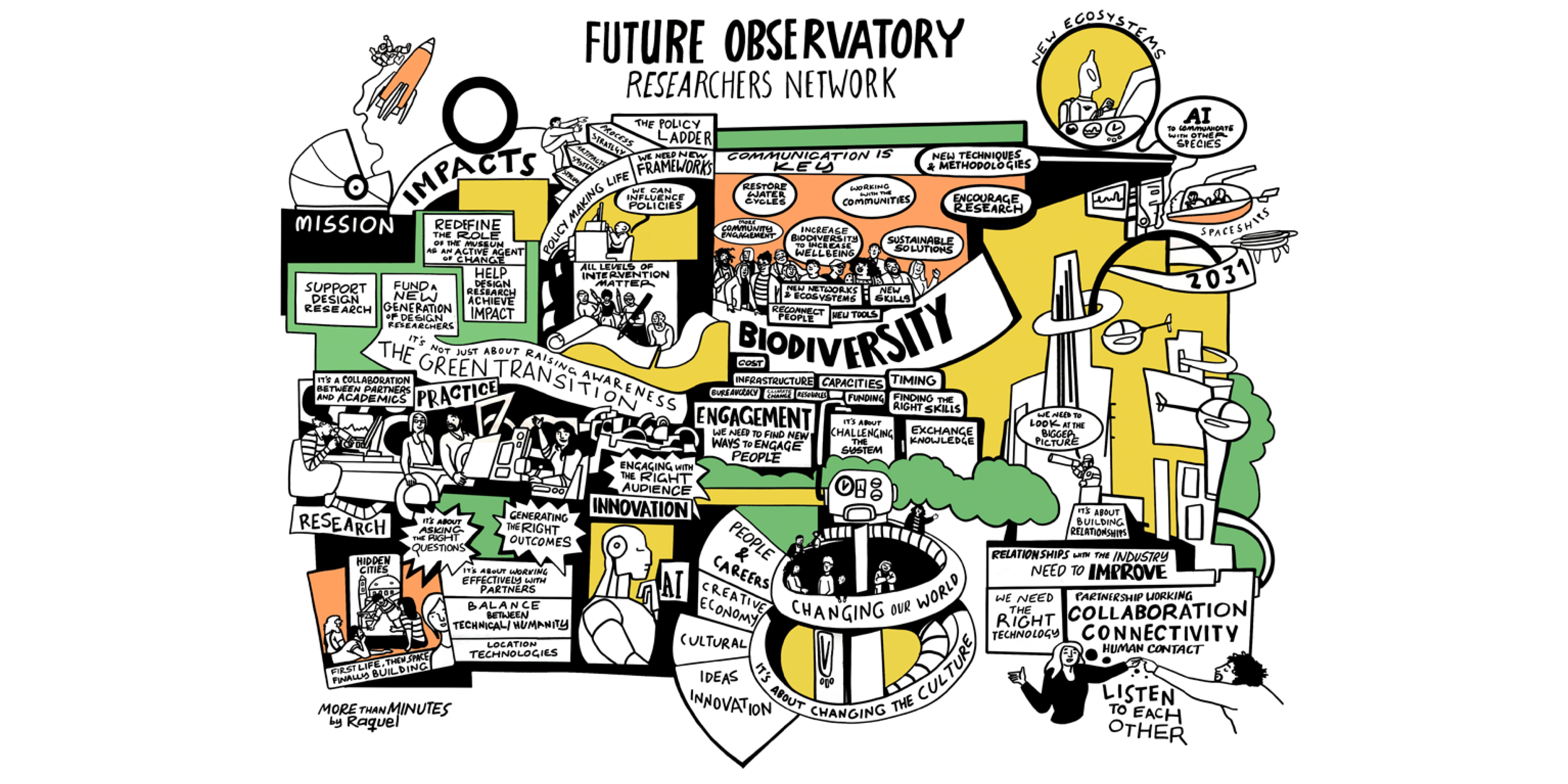

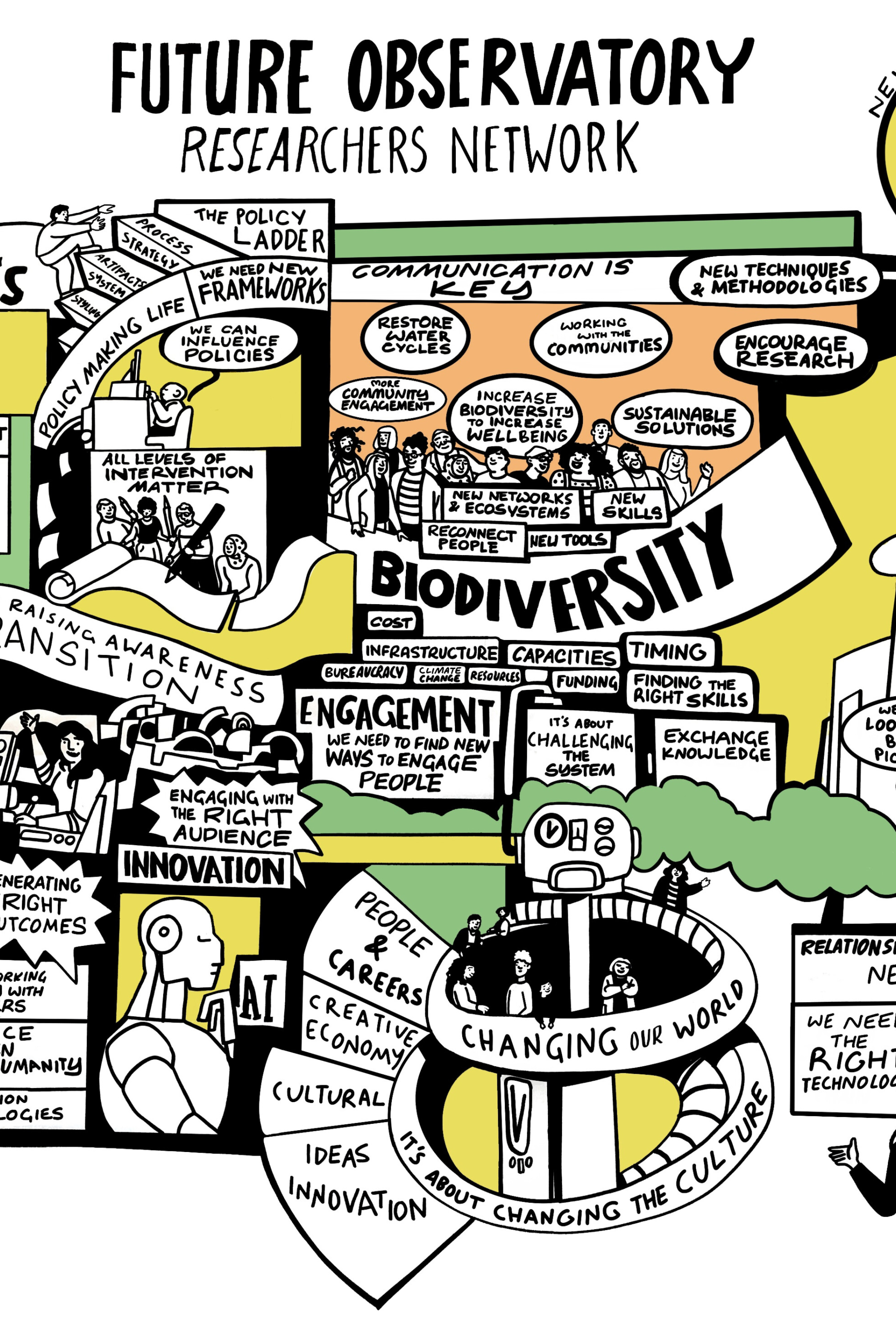

The key question of the day, however, was ‘What is the potential legacy of a research project?’ To guide us through this question, we invited Malcolm Hamilton and Nia Evans from public engagement studio Play:Disrupt to lead an interactive workshop. Their method involves using play interventions and storytelling techniques to visualise future scenarios. Positioning us in the year 2031, they invited our researchers to imagine the long-term impacts of their current research projects. Arts and crafts materials were then supplied for attendees to get creative and build physical representations of their visions for the future. The result was a series of abstract formations, visual metaphors and imaginative narratives which showcased our researchers’ ambitions and missions.

One team, whose research project explores circular models for human hair waste, used the workshop to imagine a future in which their research proposal had become a reality. The vision they presented – involving national holidays for head shaving and international infrastructures set up for mass hair recycling – offered a glimpse into a society restructured around improved natural resource and waste management. Another group of participants used the creative exercise to imagine the future landscape of research more generally. In doing so, they asked questions like ‘What types of data will be collected?’ and ‘Which sources of knowledge will come to be most valued?’ They then proposed alternatives to existing processes, such as replacing KPIs with a value system centred around ‘kindness’, initiating a wider conversation about the ways in which research could be conducted and communicated in the future.

By shifting the focus from the present day to the next decade, we were able to pre-empt some of the challenges that might arise along the way. To identify and confront these challenges head on, Malcolm and Nia encouraged our researchers to map the milestones on their ‘Journey to 2031’. To help with this, they provided prompts such as ‘When might you enter unknown territory?’, ‘When might you struggle to be heard?’ and ‘When might you need to band together as a team?’ By asking these questions, the Play:Disrupt facilitators were encouraging a proactive approach to future problem-solving. More than this, their forward-thinking strategy was preparing our researchers to be able to overcome future hurdles and the barriers to achieving impact.

At the end of the workshop, we found ourselves asking how this exercise might affect our researchers’ ongoing work. Would project teams conduct their research any differently having attempted to project it into a speculative future? Our researchers work within limited funding periods, with associated short-term timelines. So, would their visions of the future inform any of the decisions being made in the present? That’s a question they took away with them to ponder. But there was a broad consensus that, as a methodology, engaging in long-term thinking and speculative legacies is a provocative way of testing research goals.