Design Exchange Partnerships bring design researchers together with non-academic organisations, such as businesses, NGOs or local councils, in strategic partnerships capable of addressing green transition challenges. Peat, Diesel and Seaweed: Using Poetry to Design Green Transition in Northwest Highland is a Design Exchange Partnership led by the University of the Highlands and Islands, in collaboration with The Assynt Development Trust. The project aims to engage local organisations and young people in the design of three key areas of green transition in Northwest Sutherland. On her student placement with Future Observatory, Liesl Maria Bragança spoke with academic researcher Dr Mandy Haggith to learn more.

LMB

Would you like to introduce yourself and your design project?

MH

I'm Mandy Haggith and I work at the University of the Highlands and Islands. I live up in the top left corner of the mainland of Scotland, in the Northwest Highlands, close to a fishing village called Lochinver. Norman MacCaig once described it as the “most beautiful corner of the land”, and it is.

My Design Exchange Partnership project involves a network of local organisations called Northwest 2045. They have a vision for how our local area will work towards a net zero future by 2045, considering a broad range of sustainability and community issues. I am doing a poetic inquiry into some of the topics that are of local interest but have so far been unexplored. These include the potential for managing and restoring peatlands as a way of sequestering carbon, finding alternatives to marine diesel and exploring the scope for seaweed to be a part of our green transition. I am doing interviews, holding creative events and then producing poetry from the results. This will feed into a digital hub that the Northwest 2045 partnership is using to engage people with issues around the green transition.

LMB

You speak about peat, diesel-alternatives and seaweed as being key to delivering a greener future. How can they each aid the green transition?

MH

Firstly, we are in a very sparsely populated area of the world with a lot of bogs which, if well managed, can absorb a lot of carbon that can be stored in peat. This is a really, really, valuable way for us to achieve our carbon sequestration potential. When peat bogs are mismanaged – in particular, if they have eroded or if they have been drained inappropriately – then they emit methane which is a really dangerous greenhouse gas. We want to make sure that where our peatlands have been damaged, the managers of those lands are aware of the opportunities for getting grants and doing the work to get the land back into a position where it is absorbing carbon again. We have some really nice examples of community bodies that own land and are actively doing the work to restore the peats. It is quite an inspiring story to tell.

Secondly, diesel is interesting in the marine environment. We have the most northerly fishing ports in the UK; pretty much the most northwesterly fishing ports in Europe, apart from those in Iceland. There are a lot of big fishing boats in the North Atlantic that come into our harbours, fill up with diesel and then go back out to sea to carry on fishing. But alternatives like hydrogen could be a low carbon way of running the fishing boats. What do we need to do locally to provide the infrastructure for those boats to be able to fill up with alternatives to diesel?

The third area is seaweed. Being on a coastal strip, we have seaweed beds which absorb a lot of carbon. There is also a lot of excitement around the potential for that to generate jobs for people growing seaweed and produce high-value products like, say, cosmetics or food products. There are opportunities for young people to come up with new ways of making a livelihood that are green.

These three topics are all kind of hidden: the carbon in peat is underground, the diesel is out at sea and the seaweed is under the surface of the water. So that is the common thread that brings these things together.

LMB

You use poetry to convey your work. Why did you choose this medium of expression and how does it help convey your project?

MH

Poetry is really powerful because it does not make any kind of distinction between the heart and the mind. Good poetry is both thoughtful and engages the emotions.

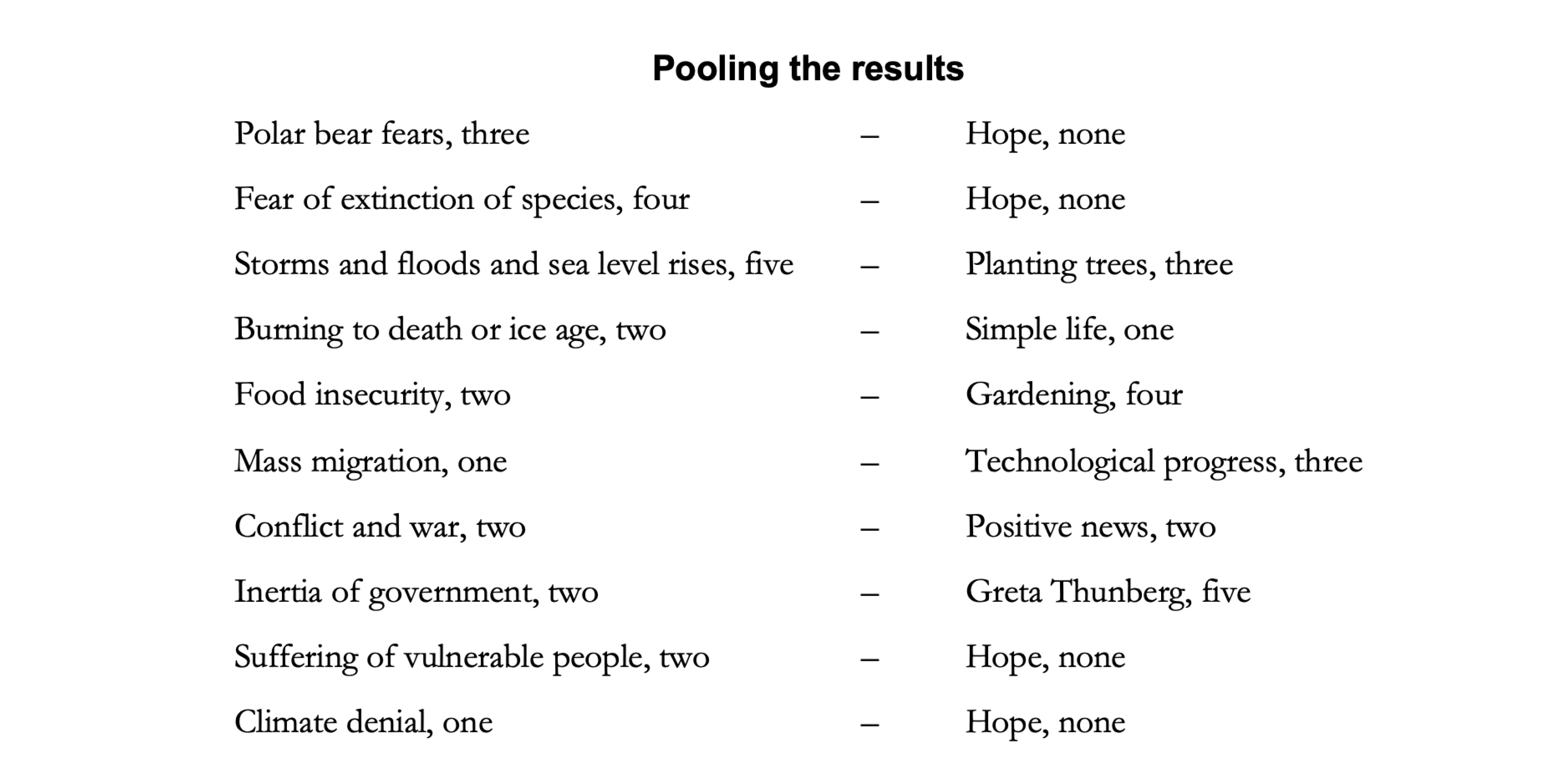

One of the things that I am very struck by when working with young people is how many of them have very strong and often very negative emotions around climate change. There's a lot of fear, despair and sadness about loss of species, and there's anger at our generation for leaving young people with the world in such a fragile state. I think poetry enables us to make sure that that emotion is right at the heart of the research.

A good poem can take you to places you are not expecting. So, I am hoping that poetry can be a way for people to find some hope, some sort of inspiration for the future.

[This poem combines themes from answers to questions about people’s worst fears about climate change (left hand column) and what hope they get from climate actions (right hand column), to which four respondents said ‘none’. The other numbers refer to how many people mentioned that theme. The questions were part of an online survey in the Peat, Diesel and Seaweed project.]

LMB

How did the partnership between the University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI) and the Assynt Development Trust develop?

MH

I have lived in this community for 24 years, so I was aware that the Northwest 2045 partnership was forming and took part in the consultations that they ran to develop their vision. I was really inspired by the fact that our community was taking climate change seriously and I wanted to help in some way. For me, it was a matter of starting to have conversations with people in the network and ask “how can the University of the Highlands and Islands help here? What might we be able to do?” I convened quite a few conversations online where I invited people from the Northwest 2045 Partnership and other people within the UHI to come and discuss how we might be able to help as a university. My project is one of the things that emerged from those conversations.

The Assynt Development Trust is one of the network’s member organisations and they act as the fiscal hub, if you like; they manage the money for the overall network. They are based in my local village so the conversations kind of evolved naturally and because of the proximity, it felt like a really nice partnership. One of the things the University of the Highlands and Islands is uniquely able to do is be embedded in rural communities. Whereas most universities are in urban environments, ours is predominantly in little communities and there is a very strong commitment in the UHI to supporting them. I like to use the term ‘communiversity’.

This partnership felt like the perfect way to ensure that the project was not just a piece of research that would happen in the university, extracting data and taking it away, but that it would work hand-in-hand with the local community. The research results are then owned by the community; hence, I think these partnerships are really powerful.

LMB

How do you see the future of this project?

MH

There is a body of poems that is emerging and there will be more before the project finishes. We are looking at how we will be able to share the poetry in some unusual ways, such as doing some light projections in the winter when we have long dark nights. There is a big building at the harbour we can maybe project onto. And there is a digital hub that the partnership is building where the poems will reside. One of the other members of the network has volunteered to take some of the young people and their poems to the Scottish Parliament so that some of the political leaders can hear the poems and get inspired by the local people's views on climate change and what they want to do about it. So those kinds of things are all in the planning stages at the moment.

I guess there is still a question mark around the fact that we are not going to solve the climate change issues in the course of this project. So, what should be the next step? That will be an interesting conversation, once we are drawing things to a close. One potential is to apply for some more research funding to do a follow-on project and help to answer some of the questions that are coming out of this one.

Liesl Maria Bragança is an architectural designer and researcher currently studying for a Master’s degree in Architecture at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London. This work was produced as part of a student placement with Future Observatory from July to September 2023.

*The interview has been edited for length and clarity.